Original Article - Original Article - Memetic Index - Memetic Glossary

Introduction

People often find interactions with children to be problematic. Making rules for them, getting them to behave the way you want them often seems to go wrong. One problem may be the illusion that as a parent (or teacher or other adult) one has "absolute authority" or "absolute control" over what the children are going to do and how they are going to act. I've written elsewhere that this is a delusion to which corporate managers and others regularly succumb. It is very likely just as much a problem in organizations like the military. Just because you're paying them, or because they've sworn an oath, doesn't mean they have to do what you "expect them to do" or even what you tell them to do.

There's a second problem with children, and that is that they may not share the same priorities and objectives as their grown-up counterparts.

Children often don't have to worry about jobs, schedules, balancing checkbooks, and so on. My thesis is that children's main priority is "keeping the attention of the parents." This is a concept that is easy to define precisely, and to evaluate, in macromemetic terms, but may be more fuzzy otherwise. The child needs to feel a sense of memetic enlistment at all times. This means that they must feel that at all times they are able to deploy some meme (preferably from an arsenal of them) that will reliably get a reaction from the parent (12). If their memetic enlistment dips to a low ebb, panic sets in immediately.

The reason for this is simple, and it doesn't really apply to adults. Adults are "independent." Children are not. Children instinctively know that if their parents abandon them, they will have no food (either from the breast or otherwise), the wolves will come with no one to drive them off, and they will die. Examples in nature are everywhere. Little birds in the nest will "peep, peep, peep" so their parents will hurry back with food. Obviously, this also attracts predators, but the youngster knows that being abandoned by the parents equals death just as surely as a predator (1).

Don't let's quibble about this one too much. Yes, of course, children have other priorities and interests. However, nobody would be so stupid to argue that if your air supply got cut off, your interest in your favorite TV program would not at least be "suspended" until you could breathe again. There's no "oh, wait, let me just get to the next commercial break." That's nonsense. It's useful to see children as working with the same kind of priorities vis-à-vis their parents (2).

In sum, the laws of memetics apply just as well to children as to adults. One important difference is that children are typically not expected to behave a certain way under threat of jail time or deprivation of income and livelihood, as adults all are. Finally, children's lack of independence imposes on them an urgent need for strong memetic connection to caregivers, typically the parents.

The TV Time Rules

A scenario easily recognized is that of getting the kids to not watch too much television. Treating them like factory workers who only have a half hour for break and then back to work, work, work is an obvious first approach. Again, there's no threat of being fired or sent to HR as a precursor to being fired (4), which kind of works to extract obedience in a factory. Children want to watch TV, and it may be kind of an addictive activity (5), but here's the kicker: a lot of their interest may be in getting the goat of their parents! If the parents impose a rule system that guarantees parental reaction (13) if the children merely do certain things (which are usually termed "misbehaving") then the children may do unintended things and this may be on the face of it hard to understand.

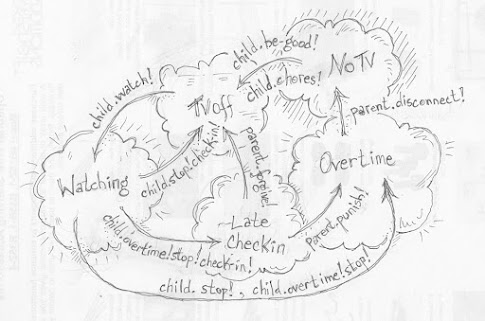

Here we have a chart (6) that describes a system where the kids can watch TV, and they're supposed to shut it off after a certain time. However, if the kiddies don't switch off the screen, the only way the parents can find out is to yell up the stairs, or to check on them. It's only when the parent checks that they know if the kids are still watching, or if they've stopped when they're supposed to (which mommy cannot know, since mommy did not see until she checked in), which may involve more yelling. If the kids are responsible for turning off the television, even if mommy or daddy yells, the kids may keep watching (7).

|

fig. 1. dysfunctional TV time memeplex

|

Note well that the meme that takes the system from Watching to TVOff is deployed by the children, i.e., "c.stop!" In other words, the parents do not have a meme that can transition into that state (more on this anon). Note also that the parents yelling does not directly have any influence on the state of the system, and we'll see a more detailed examination of how to model this in the next diagram (8,10). One final thing is the "Engaging" state. It's a "compelled state" (9), which means the parents are thrown into one of two situations without knowing beforehand which it will be, or what they will be able to do (which memes they will be able to deploy) until they get there.

Immunomemetic Depiction

Here's a diagram that explicitly shows the immunomemetic transactions (8) in this system, namely, "p.yell!c.ignore!" and "p.yell!c.whine!" (10) This notation represents how the "yell!" is what gives the kids the chance to "whine!" or "ignore!".

|

| fig 1a. TV memeplex with explicit immunomemetic linking |

What I've added from fig. 1. is that the children's "whine!" and "ignore!" memes are linked to the parents' "yell!" memes. This is an immunomemetic notation. The "yell!" meme is deployed, which immediately gives the child the opportunity (7) to deploy "whine!" or "ignore!" and the system remains in the "Watching" state, that is, it has not moved forward, the parents' arsenal of memes for moving the system in the direction they want has not changed and has not improved. The parent can continue yelling, which is effectively a stand-off, or they may "relent!" which still leaves the system with the children in control of the TV.

Let's do an macromemetic analysis of the memetic system (memeplex) as described above.

The problems with this situation include:

1. There is a compelled state.

2. there are multiple immunomemes which the child may deploy

3. There is no meme the parent may employ to get the TV off, i.e., to compel the stop! meme from the child.

#1 is bad because when the parent decides to engage the situation, she is immediately flung into one of two situations: #1 the TV is already off (unlikely) and things may or may not be cool (requiring more yelling) or #2 the TV is not off, and she is immediately engaged in a memetic melee with the child in which she has effectively no productive memes or memes which give her advantage (except just to "relent!" and get out of the situation).

#2 The child has multiple immunomemes which he may deploy in response to the parent's yelling. One is to simply "ignore!" the yelling, a passive-aggressive response. The other is to "whine!" and put off the parent's yelling with any number of verbal or emotional responses.

I use the term "opponent" somewhat lightly (^>^). Again, compelled states are bad. The "opponent" having immunomemes which prevent a change in state (or which allow transition to another state also favorable to the opponent) is bad. Having no memes to move the system towards the state you want is bad.

In sum, the parent faces a compelled state where they are thrown into a bad situation. The situation is bad because they have no memes available to move the situation to where they want it to go, and the child has immunomemes to block the ones they do. The only route to resolution (TVOff) is via a meme which must be deployed by the child. Even if the parent is allowed to shut the TV off, the situation isn't that much better, as we'll see.

What if the Parent Switches Off the TV?

In macromemetic design, the point of adding another meme is to enable a new state transition. Sometimes this will be to an existing state, often it results in the creating of a new state that the new meme permits transition to. It all depends upon what makes the most sense in terms of modeling.

Let's get to it. What might happen if we "allow" the parent to shut the TV off themselves?

The kneejerk supposition is that it would simply transition the system to "TVOff," that is, that in addition to the deployment descriptor (see diagram below) of "Watching.child.stop! => TVOff" we'd also have "Watching.parent.stop! => TVOff". Alas, probably not.

It would probably be modeled by another state, ParentTVOff, which would allow the child more memes in terms of throw-fit! or meltdown! or scream! They would be in a state where that is "allowed," so to speak, which is a valid macromemetic comment on how that functions.

|

| fig. 1b. New State for Parent turning off the TV |

The Second Law of Macromemetics tells us that any memetic deployment results in a state transition. If the parent shuts the TV off, we're in a new state. The TV is now off, the child is no longer watching it. But the parent has now given the child the opportunity to throw a fit, have a meltdown, scream and cry about it. Obviously, if the child shuts the TV off himself, such fit-pitching would make no sense. In other words, "TVOff" and "ParentTVOff" may have very different dynamics. "Feelings" are not really macromemetic concepts, as such, but now we have how the child "feels" about the parent turning the TV off as opposed to doing it himself.

What macromemetics does tell us is that it's more about how the parent "feels" or which memes the parent will resonate with if they are the actor. The child now has something he can attack the parent about, i.e., having shut the TV off. Memes are all about other agents resonating with them, even if they do nothing. The child is effectively guaranteed that if the parent has just shut the TV off that the parent will in turn engage with the child when he throws a hissy-fit about it. If the child tries to turn the TV back on, for instance, the parent will either have to let that happen, or try to stop the child from doing it. A child crying and looking for attention is one thing, but a child crying in response to something the parent has done is another. The parent has effectively created a whole new state with a whole new inventory of memes the child can use against the parent. It's yet another "Kick Me!" sign the parent has put on her own back, or as the British say, "she's made a rod for her own back."

This fresh hell of temper tantrums in the "ParentTVOff" state is only relieved when the child deploys the "child.accept!" meme and we finally make it to the "TVOff" state. In other words, the child is still in control of all the memes that lead to state transitions.

Again, it may be more about the child getting the attention of the parent and less about watching television. We see this in the memetic diagram. In macromemetics, we speak in terms of "cans" and "coulds" rather than "feelings" or "beliefs" or "motivations."

I've represented the parent switching off the television as a transition to a new state, but this event is still immunomemetic in nature. The child is "bullying" the parent once again. The response of the parent to the temper tantrum is reliable, and we could add to the diagram that if the parent disengages, i.e., deploys the "parent.relent!" meme to get out of the situation, the child may simply turn the TV back on again, going back into the "Watching" state. This process of adding states and transitions could probably go on for some time.

Reliability is key, by the way. If the child can reliably get a reaction from the parent, even a deeply dysfunctional one, it's gold, so to speak. The TV memeplex seems to supply this in spades.

Redesigning Our Way Out of Memetic Hell

C

heck out my essay for some contrast with a more functional system, which I'll touch upon here.

|

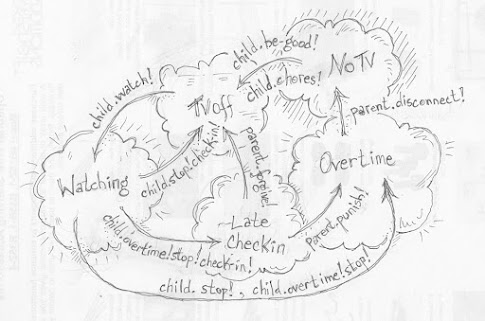

| fig. 2. A redesigned TV memeplex |

Please check my other essay for a detailed discussion of this memeplex, but some key elements are that they parent does not have to check up on the children. The children are expected to switch off the set themselves at the appointed time, and report to the parent that it is done. Failure to do so results in possible punishment in terms of NoTV for some period (the set may be physically removed, or other such). An additional, optional, angle, taking things a step further, is the "child.chores!" or "child.be-good!" memes which must be satisfactorily performed to get the TV back (TVOff, the only state from which you can get to the "Watching" state). In other words, the parent doesn't have to do anything, and is not in the position of "giving the TV back" to the children. If the children don't want it, they don't get it, the parent can hang back. Another suggestion I make is that the punishment be drawn out of a hat, or the number of days of no TV is the roll of dice.

Another advantage of the system of the children checking in themselves is that the parent can reward them with coupons for more TV time later if they finish early, and such coupons could effectively become a reward currency, given out at other times, and could even become a medium of exchange between siblings, allowing them to

form alliances more easily. A child could even save up these coupons and use them for an all-Saturday-long "movie marathon" with friends or siblings.

Obviously, none of this is even remotely possible in the "old system."

What we see in the new system is no immunomemetic interactions between child and parent. There are no compelled states where the parent is forced to do something in order to reach her goals, or dependent upon a child doing something (like "child.stop!" turning off the TV). The parent is not even compelled to mete out punishment at the moment of misbehavior, but it is perfectly well understood that the parent has the option, and she may decide to be merciful this time -- it's all up to her. In other words, the children's good or bad behavior enables immunomemetic response (enables "bullying behavior") on the part of the parent, which they may exercise at leisure, and not the other way around.

This is the way it should be. Children should be made to understand what they are expected to do (watch TV for an hour or less a day, and shut off the TV when done, then tell the parent), parents should be able to expect good behavior on the part of their children, and if there is a problem, the parents should be able to take clearly defined action, which the children should be expecting.

One takeaway is that TV watching is not important. It is a dumb "hill to die on." As I said earlier, children are not employees, and it's impractical to treat them as such. They are motivated by parental attention over material rewards. Just saying "I'm giving you this, so you do this," barely works with money and jobs for adults, and it probably has very little relevance to children.

Again, if a parent is having to "make" their children do almost everything, then something is desperately wrong. Parents are lucky, because unlike employers, they have total control over the most powerful resource there is: their own love and attention for their children. If that can be focused and directed such that the children get good, positive attention instead of the parent trying to apply negativity to get what they want (and which is probably ineffective anyway).

Contrast these two:

Child: "Hey mom, I'm done watching TV"

Mom: "Oh, you're such a good boy to tell me. You finished early. Let me give you a 15-minute coupon."

[ physical affection is possible here, too ]

Mom: "Turn off this TV NOW! You've already watched too long!"

Child: "But mom, we're almost done with this show!"

Mom: "I don't care! Rules are rules! Shut it off and get ready for bed!"

Child: "Whaaaaah! I don't wanna!"

...and so on...

One thing that can be designed in is things like "reward and praise opportunities." If as part of the TV memeplex, the child can ask permission to watch TV, the parent then has the opportunity to agree, and when the rules are followed, if the parent doesn't have to enforce them, then the parent can offer praise for following the rules. If the parent is the enforcer, then everything always starts out on a negative initiating action, creating an opportunity for a negative reaction in return.

Summary & Conclusions

Macromemetic design principles can be applied to setting "rules" for children. Which memes are the children able to envoke? Which do the parents want them to? If action on the part of parents opens the door to immunomeme use by the children, this is bad. Things like "no back talk allowed" are draconian and heavy-handed, but effectively examples of this. Better memetic pathways may be designed.

Children will use what they have at their disposal, regardless of intension. This is in keeping with the Second Law of Immunomemetics.

A sober analysis of memetic states and memes that cause transitions is called for. The parent should think in terms of what they want to have happen, work it out so that the children are taking most or all of the action themselves, and that if the parent needs to, or can, take action, that it be exceptional, and at the parent's leisure, and not forced (no "compelled states"). The children misbehaving should create a state where the parent has an inventory of memes to draw upon, which are well-known to the children in advance (such as taking away the TV for a week). The children's (bad) behavior should not force the parents into action, and the children should not have counterattacks to this. Consider the difference between the confrontation of switching the TV off in front of the children and non-confrontation of the kids finding out later that the TV has been unplugged (as a result of their bad behaviour earlier).

Finally, unlike an employer who pays for work, a parent can offer her attention and love. By providing opportunities for the child to interact at a high level with the parent, and receive a reliable reward in terms of a memetic response, and tying this to the desired pathways in the memetic system, or memeplex, being designed, good behaviour is assured, and children are less predisposed to bad behaviour.

Finally, reliability of parental response is key, whether it's in response to good behaviour or bad. If children cannot get the parents to reliably pay attention to them for any good behavior (or just in general), either because the parents ignore them or take good behavior for granted or no "specified" forms of good behavior exist (as in our designed memeplexes here), but bad behavior brings guaranteed parental response, then children will have an incentive to behave badly.

____________________________

Bibliography

___________________________

Footnotes

(1) This fear of abandonment can lead children to do some otherwise hard to explain self-destructive things: self-harm, self-endangerment, general misbehaving as we'll see, and so on.

(2) I've found, and I've had others recognize the same thing, that children have a kind of "egg timer" in their heads, and they can go for a couple of minutes in a state of "disconnectedness." Try it for yourself--I'm not sure if I can define the "egg timer effect" without diving into macromemetic terminology and theory. This is the kind of thing that leads us as parents to go to the toilet with our children, take baths with them, watch all of their kiddie TV programs with them (3) and so on.

(3) This is a tangent, but I've found that children are perfectly happy watching adult-oriented programs. They don't find them boring or "over their heads." As mentioned, kids like to feel connected to their parents. They feel panic and fear of death if they lose memetic contact with their parents, more so than if deprived of singing purple dinosaurs.

(4) Obviously this is an oversimplification of the incentives present in a workplace environment. Still, "I'm paying you, that's why!" and "I'm the mommy, that's why!" are perhaps not so far removed.

(5) I tend to favor the Kiwi term "more-ish," as in "Oh, these crisps are more-ish -- I can't stop eating them." Addiction is a medical term, and its overuse in the vernacular borders on the offensive, oftentimes.

(6) A memetic state transition diagram. The clouds represent "states," the arrows "memes," and the labels on the memes are "deployment descriptors" (10). The "lightning bolt" on a state cloud indicates a "compelled state" (9).

(7) As we'll see, the children not responding to the parents demands to turn off the TV, ironically represents a "bullying opportunity." Or rather, the parents' yelling for them to turn it off represents one, since it gives the children a chance to ignore them, making them yell more, or whining, which is engaging the parents on the children's terms, and the result is that the set stays on. (8)

(8) "Immunomemetic deployment opportunity" is another name for a bullying opportunity. An immunomeme is a meme that serves to keep the memeplex in its current state, i.e., to defeat the attempt by other agents to shift the state away, like the parents' attempts to shift the system from the kids watching TV to the TV off and the kids getting ready for bed. The way this system is set up, the parents' memes to tell the kids to quit watching TV give the kids an opportunity to deploy immunomemes which they didn't have until that moment. Effectively the kids are bullying the parents and the parents are walking right into it.

(9) See

glossary. A compelled state is one where one must immediately transition out to another state or specified list of possible states and one is forced to deploy certain memes to do so. Think of a school test or an encounter with a police or court interrogation.

(10) Notational note. A meme is expressed by a "deployment descriptor" which takes the form of "State.agent.meme! => NewState". In our examples we see things like "Watching.child.stop! => TVOff" where the child (represented by "c" for compactness) deploys meme "stop!" which effects the transition from the memetic state of "Watching" to that of "TVOff". "Immunomemetic notation" is where memes stack up (11), as in "Watching.parent.yell!child.whine! => Watching" (again, in the diagrams we abbreviate "parent" the agent as "p"). The parent deploys "yell!" which then gives the child the opportunity to "whine!" which keeps the system in "Watching." Note that there is no "Watching.parent.yell!child.stop! => TVOff" transition. The child always has the opportunity to turn the TV set off, and so is not "enabled" to do so by the parent yelling. Furthermore, the child can choose not to "stop!" the TV for as long as he wants.

(11) This same notation works for "

alliances," too, by the way. See

Glossary. A "benefactor" or "mentor" deploys a meme which then allows a "beneficiary" or "protegee" to succeed where they would otherwise not be able to. For instance, cooperating and helping while playing a team sport: "Play.mentor.pass!protegee!score! => Goal" One could even think of "Play.protegee.run-downfield!mentor/pass!protegee!score! => Goal" This string of linked deployment opportunities implies a "hidden state" or "virtual state" or as in our examples, a "compelled state" (subtle difference). For instance, "Play.progetee.run-downfield! => ProtegeeOpen" at which point the mentor has the opportunity to "ProtegeeOpen.mentor.pass!protegee.score! => Goal" The state of "ProtegeeOpen" is thus "hidden" by the longer meme deployment string. The subtle difference between the "hidden" state and the "compelled" states in our examples is that the mentor is technically not obliged to throw the ball to the protegee, and indeed may have other choices (including doing nothing). The "Engaging" state in our examples is a compelled state, since the parent is forced to transition to one of two states immediately, but it is also a "virtual state" in that it's a target of a transition from some state, the "Waiting" state in our example, and it results in another state, either "Watching" or "TVOff," but no actual meme is deployed to make this transition. In sum, "compelled," "hidden," and "virtual" are all similar classes of state, with subtle differences that determine their use.

(12) A "reliable reaction" in memetic terms is "reliable memetic resonance" from the parents. See

glossary for discussion of resonance. An agent deploys a meme, and another agent "resonates" with that meme (such as a native speaker recognizing a word in his language, or laughing at a joke). A joke that nobody laughs at is an example of failed resonance. Resonance is revealed by agents deploying memes in response to the resonated meme.

(13) Systems of rules are addressed by the Second Law of Immunomemetics which holds that a system of rules translates directly to a system of immunomemes ("bullying opportunities"). Authority figures often make the mistake of setting up a system of rules and then lamenting that there are lots of immunomemes ("bad behaviours" or "subversive behaviours") that crop up as an unforeseen result of their "rules." You have to design what you expect people to do, and which people, and just writing out a rule, like "don't be a dick," or "don't watch too much TV" doesn't cut it. It may cut something else, but it may not be what you expect. This is a very important idea.

No comments:

Post a Comment